By John Walley, chief executive, NZ Manufacturers and Exporters Association

The government has recently announced its goal of lifting exports from 30 percent to 40 percent of Gross Domestic Product, and it is clear from our export make up that much of this will have to come from added value activity (the growth of farming and tourism is limited by resource constraints).

The goal is necessary but the problem is that the policy settings that have prevented growth in added value exports seem to be missing from the export review.

Inflation targeting, coupled with the myth that nothing can be done with the exchange rate, has taken on almost religious stature in New Zealand. Of course, it is not an immutable law of nature and options exist in macroeconomic management. If you doubt this take a look at what the Swiss have done over the past year. Switzerland is slightly bigger than New Zealand and has a few other advantages but there is no difference in kind between the two economies, just the government and central bank thinking are worlds apart.

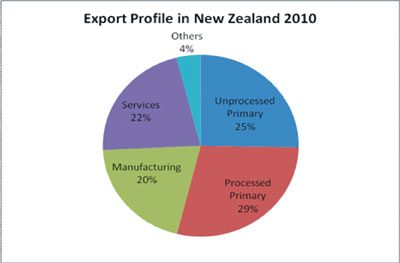

As Figure 1 demonstrates, our economy is split into four parts: services (mostly tourism), unprocessed primary, processed primary and manufacturing.

Essentially half of our exports are products with a value added component (manufacturing and processed primary) while the other half involves the low cost production or supply of our natural advantages. If we look at it another way and compare firms from various export industries the differences are apparent.

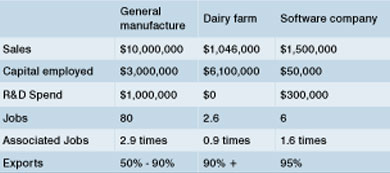

Dairy farm numbers from DairyNZ Economic Survey 2010-11. Associated job numbers are from the Economic Policy Institute, Updated Employment Multipliers for the US Economy (2003).

It is clear from the table that a farm does not add much value to the economy in itself. The major benefits to New Zealand occur where those commodities are used as inputs to make a more valuable product with the kicker of more dependent jobs, research and development spending, and more associated economic activity.

So why aren’t we seeing enough firms jumping into added value activity?

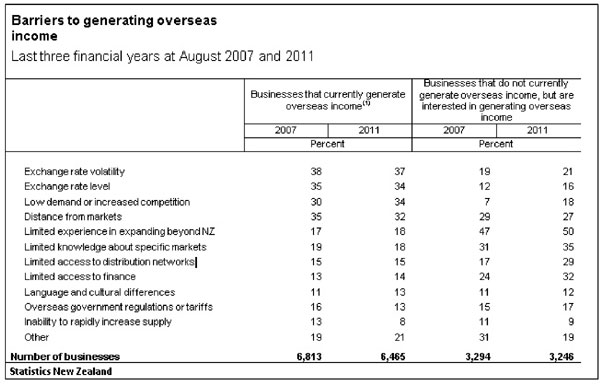

The Statistics New Zealand table (Figure 3) quizzed exporters on the obstacles to generating more export income. The first two were the exchange rate and the third is heavily inf luenced by the exchange rate.

For firms chasing added value to food products this exchange rate impact is often a double whammy as high commodity prices usually bring a higher New Zealand dollar. That means they will pay more for their main inputs and get lower margins when they sell their product overseas.

Those manufacturing firms adding value must invest in long term development – that means expensive plant, skills and staff development. This long-term investment requires greater certainty and better margins to make the outlay worthwhile. The current policy framework drives a volatile and overvalued exchange rate amplifying uncertainty and lowering returns to export activity. This is a stealthy problem; while the companies are still there seemingly all is well, but absent investment does not create growth – this is a key point often forgotten by politicians. At a recent gathering where Bill English spoke he glossed over this problem and commented that he was happy to see companies still operating; he should be concerned about why they are not investing.

There is no doubt that while current macroeconomic settings persist, the lower the value added in New Zealand the lower the foreign exchange risk.

There is little point conducting an export review or having export growth targets if the policy does not address the problems that are clearly identified. It might work in politics but not in the real world.

Commodity production must be accompanied by value add and complex industrial activity to achieve significant growth in exports.

New Zealand’s macroeconomic policy framework has featherbedded high debt, low revenue, low wage activities (farming and property investments) and the effect is manifest in our economic performance. In spite of lip service to the knowledge economy and high value activity our policy choices demonstrate our true values.