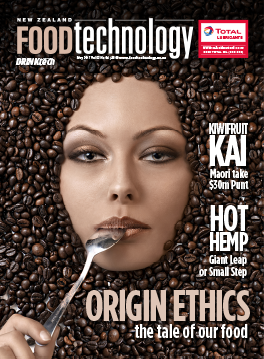

By Gary Hartley of GS1 New Zealand

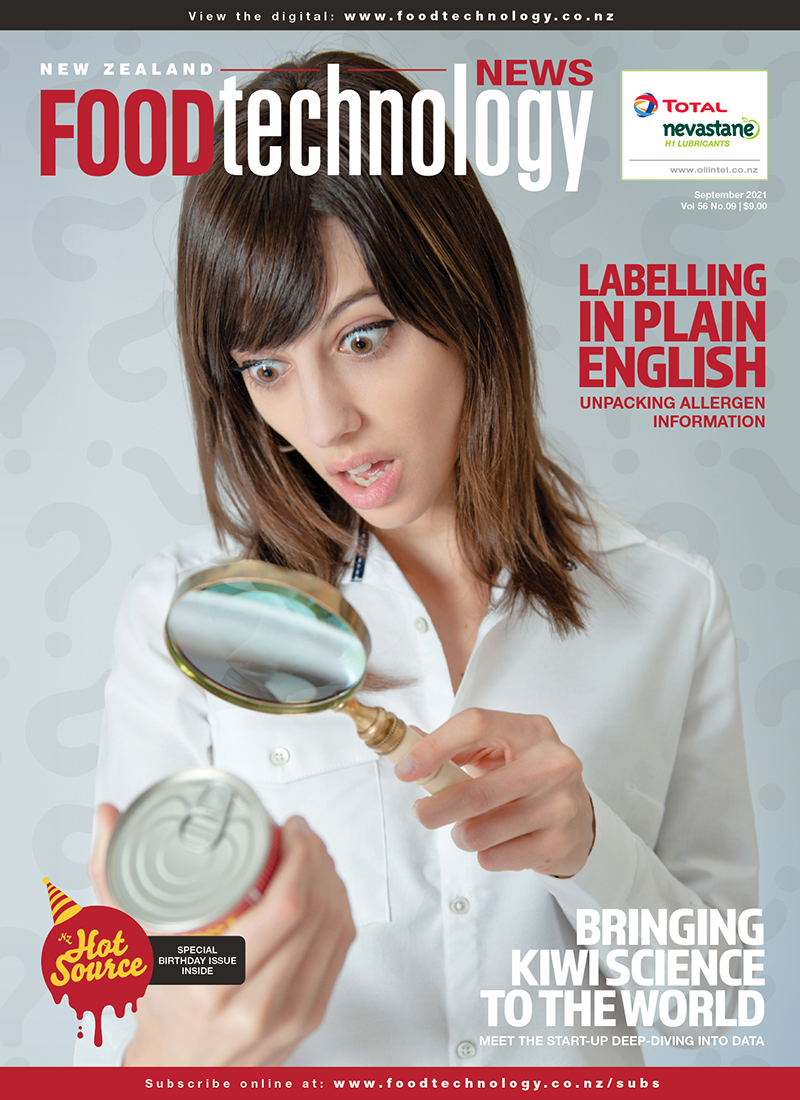

Let’s face it, consumers are getting smarter. They demand to know more about products before they buy and they access information from an increasing array of sources.

Indeed, the value of products could come to rely more and more on what is known about them – and that will come down to the quantity of product related information available in the marketplace at any given time and to the veracity of that information.

The ‘savvy shopper’ is a new category of consumer of great interest to marketers in Europe and North America: shoppers who are more informed than ever before, who actively benchmark products on price and attributes, and who factor in other social and environmental considerations.

They use diverse channels to find out what they want and to make purchases. Obviously, the trend to ‘savvy shopping’ is being accelerated by the ubiquity of smartphones. (Recent figures in the UK suggest one in three consumers now owns a smartphone and who would doubt that New Zealand is far behind).

The rise of this type of consumer – herself a product of the digital age – could push us all into rethinking the nature of supply chains. International business consultants McKinsey talk now about the ‘value delivery system’ in which businesses are, essentially, identifying value that is or will be sought by consumers, creating that value through their design and manufacture of products, and then communicating it through price signals and other information provision.

The traditional view of supply chains puts an emphasis on making, distributing and selling products, with rather less concern for the value of products to active and discerning consumers.

What are the implications of communication becoming a more critical component of supply and value chains?

For starters, more information on labels and packaging: we see that, for instance, in the growth of ingredient and nutritional data on food products over the past 15 years or so.

But there is also greater need for communication among trading partners so they can all cope with market information demands, and for use of diverse channels to reach consumers. Further, the product information being communicated must be meaningful and accurate – hardly guaranteed as products, supply chains and consumer demands become more complex and diverse!

Tomorrow’s supply chains – call them value chains – will require trusted sources of information: sources that can be relied on because they are transparent and verifiable. In business-to-business communication, this is the already wellestablished role of the GS1 System worldwide.

Standardisation of product, place and logistical unit identifiers, and of formats for data collection and communication go a long way towards ensuring the veracity of information.

In this sense, the GS1-created Global Data Synchronisation Network (GDSN) is a critically important trusted source of information: a network of databases into which a company publishes its data once for access and use by many others. The GDSN now supplies verified data about over nine million products worldwide.

But what of communication with those savvy shoppers? What are the trusted sources they need to access meaningful and accurate data and information in consumer markets? Much of it is published directly by brand owners, by definition trusted sources. But the world is seeing proliferation of information from third parties as well, driven by the ease of digital media.

Smartphones in particular are exploding information availability about products and services. A recent UK study, by GS1 and the Cranfield Business School, found smartphone applications (apps) were 100 percent accurate in providing information on a sample of products when a brand owner was the source, but only nine percent accurate when it was a third party. There are thousands of apps available many of them with barcode scanning capability – potentially thousands of data sources.

The issues are compounded when consumers access information comparing one product with others, or analysing a product’s origins and qualities. Here’s an example related to the environmental issue of ‘embedded water’: WWF published on the web figures to show that the average cup of latte in the UK required 208 litres of water to produce (coffee and milk production etc). A fascinating number but can we trust it? (No disrespect to WWF).

Trusted data sources – watch for them to become increasingly valuable players in a world of complex supply chains and savvy shoppers. They could become like reliable friends who, as the old proverb says, are like cool drinks on a sweltering hot day.